How Art Theory Helps Me Spot Corporate Scandals Before They Unfold

Learning from the visual art approach to paint a clear picture of a company's true nature

Dear Reader: Welcome to my newsletter! On this piece: What lies in the shadows of investment analysis? Beyond management presentations, financial statements, and compelling narratives, critical insights are often hidden. When analyzing a company, what should be there but isn't? Which questions remain unanswered? Today, I explore how examining these gaps - the negative spaces in business analysis - can deepen our understanding of companies. Let's begin.

M.C. Escher's 'Sky and Water I' (1938) is a prime example of the concept of negative space. In this woodcut, Escher seamlessly transitions between images of birds and fish by utilizing the negative space between them.

The birds at the top of the artwork gradually transform into fish at the bottom, with the negative space around the birds forming the shapes of fish and the negative space around the fish forming the shapes of the birds. This interplay creates a really interesting visual metamorphosis that highlights how negative space can be as significant as the positive forms in a composition.

Artists have long understood that what isn't there can be as important as what is and just as negative space defines boundaries between visual elements, gaps in information while looking at a company can reveal more than the data itself.

So, how do we look for what isn't there? I've divided this article into four sections:

What Lies Beneath, Missing Pieces in Financial Statements: Looking a little bit deeper into financial statements.

Spotting Hidden Signals During Earnings Calls: Trying to focus on what management is NOT saying during earning calls.

A Call-to-Action For an Active Approach: A dose of healthy skepticism.

Conclusion: Some final thoughts.

What Lies Beneath: Missing Pieces in Financial Statements

"What the human being is best at doing is interpreting all new information so that their prior conclusions remain intact."

-Warren Buffett

As you may already know, there’s always more than meets the eye while analyzing financial statements. Some of this is deliberate, some is structural, and some emerges from the natural complexity of modern business operations.

Next, we'll explore two key areas where financial statements often fall short:

Corporate Disclosures: A Closer Look

The Good, the Bad, and the Unaccounted For: Hidden Assets and Liabilities

Corporate Disclosures: A Closer Look

Again, there are many ways in which companies can muddy the waters. Let’s take a look.

Disclosure Shrinkage Pattern

As the title suggests, this refers to a pattern where companies begin reducing the detail in their financial reporting before significant business challenges arise. Hey, there could be perfectly valid reasons for those changes, just make sure to understand them.

Now, which type of changes I’m referring to? Three patterns to watch here:

Segment Consolidation: The most common form of disclosure reduction involves consolidating previously separate business segments. The key insight isn't just the consolidation itself, but its timing - it can occur just as competitive pressures begin mounting.

Geographic Detail Reduction: When companies start reporting fewer geographic breakdowns, it could signal problems in specific regions.

The space to make adjustments has to be within regulations, as there must be compliance with the rules.1

Incomplete Footnotes

Let's continue with incomplete footnotes. Have you ever seen companies that provide increasingly vague disclosures about critical accounting estimates?

Yes, footnotes can sometimes be vague or incomplete, hindering a full understanding of the company's financial health.

To ensure a comprehensive look, we should ask the following questions about the footnotes:

Clarity and Consistency: Are the footnotes clear, concise, and consistently applied across different accounting periods?

Materiality: Do the footnotes adequately disclose all material information relevant to the financial statements?

Assumptions and Estimates: Are the assumptions and estimates used in the footnotes reasonable and supported by evidence?

Contingent Liabilities: Are all potential contingent liabilities, such as lawsuits or warranties, adequately disclosed?

Related Party Transactions: Are all related party transactions disclosed, and are they at arm's length?

Comparing the footnotes disclosure with close competitors is also another good practices to better understand this type of information.

Changes in Accounting Policies

Changes in accounting policies represent another area where the negative space in financial statements becomes particularly telling.

The key is to ask:

Rationale for the Change: What are the specific reasons for the change in accounting policy? Is it due to a new accounting standard, a change in business operations, or other factors?

Impact on Financial Statements: How will the change affect the company's income statement, balance sheet, and cash flow statement?

Comparability: How will the change impact the comparability of the company's financial statements with prior periods and industry peers?

Timing of the Change: Is the timing of the change appropriate? Are there any potential motivations for the change, such as to improve reported earnings or to mask underlying problems?

Auditor's Opinions and Critical Audit Matters (CAMs)

This is an interesting one. Since 2019, under AS 3101, auditors are required to disclose Critical Audit Matters (CAMs) in their reports. These CAMs highlight areas where they believe there may be significant risks or uncertainties related to the financial statements.

Let’s look at Under Armour example. Turns out PWC issued a CAM about the criteria the company was using to recognize customer returns an allowances.

Well, they had to issue something beginning 2019, even if they observed the issue years before.

What had happened? The company's "reserves for returns, allowances, markdowns, and discounts" account showed suspicious patterns:

In 2016, while gross sales increased by 22.5%, the reserve account jumped by 54.71%

In 2017, despite gross sales only growing by 5.1%, the reserve account surged by 68.67%

Under Armour was employing questionable practices to maintain its sales growth. Allegedly, they were:

Pressuring customers to accept more products than needed

Offering steep discounts as incentives

Allowing customers to return unsold merchandise in subsequent quarters

"Truckloads of unopened boxes would come back" according to reports2

The SEC investigation revealed that Under Armour had:

"Pulled forward" $408 million in existing orders over six consecutive quarters

Failed to disclose that this practice created significant uncertainty for future revenue

Used these tactics to meet analysts' revenue estimates3

So, was this example a case of negative space? Well, you could argue that there were missing disclosures about how they were recognizing that revenue, and that this was confirmed by the CAM.

Regardless, paying attention to CAMs can significantly enhance due diligence for analysts and investors by highlighting areas that require further scrutiny.

Let’s look now at hidden assets.

The Good, the Bad, and the Unaccounted For: Hidden Assets and Liabilities

While our previous discussion focused on examining negative space - those telling gaps in financial disclosures and the nuanced ways companies present (or omit) information - let’s now explore another dimension: the hidden assets and liabilities that typically remain outside traditional financial statements.

These items often escape formal accounting recognition due to regulatory constraints or the inherent difficulty in quantifying intangible value. Yet, they can significantly impact a company's financial position, either as powerful value drivers or substantial obligations.

Assets

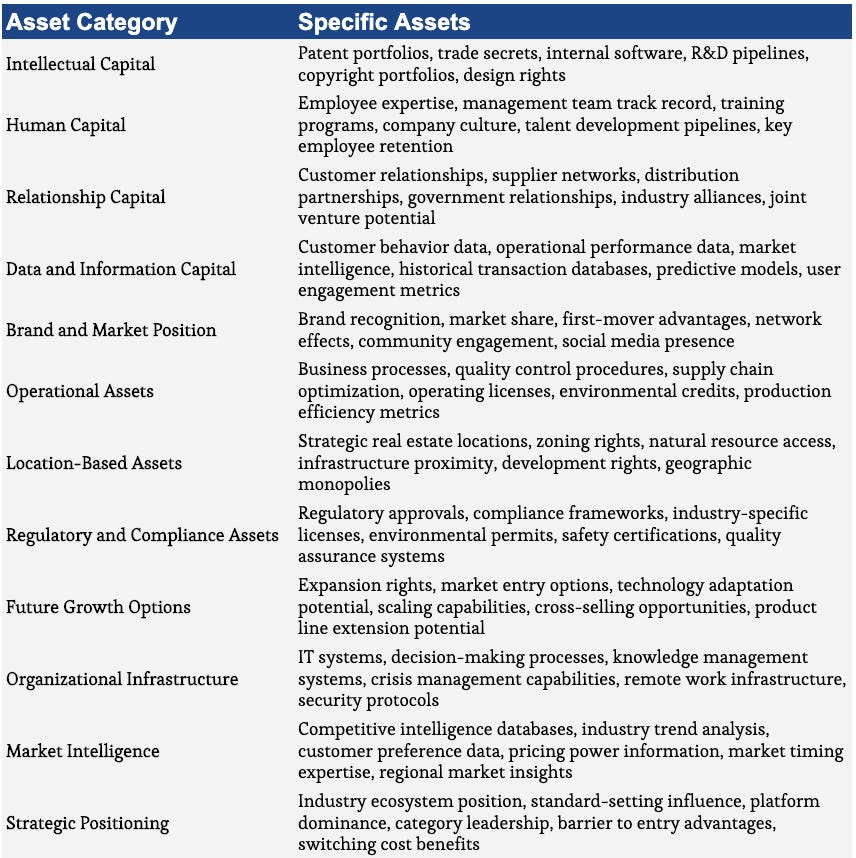

Which types of assets are not accurately reflected on the balance sheet but can significantly contribute to a company's value? I think here we will squarely fell under the category of intangible assets.

Granted, the value of these assets will become apparent during mergers and acquisitions, when acquirers typically pay significant premiums over book value to access these hidden assets. Nevertheless, we should also consider different accounting treatment in different countries.

Under US GAAP (ASC 350): The general rule is highly conservative - most internally developed intangible assets, including customer lists, must be expensed as incurred. This stems from FASB's skepticism about the reliability of measuring future economic benefits from internal development projects. The philosophy here prioritizes accounting conservatism over economic substance.4

Canadian Standards (ASPE 3064/IFRS): The Canadian approach, particularly under IFRS, is more principles-based and economically focused.5

I digress. So which are some assets that could be present in a company but not fully represented in the financial statements? Below is a non-exhaustive and approximate list.

Let’s discuss now those liabilities that a company may have but, again, living that negative space. I’ve separated those obligations in two groups: non-contractual and contractual liabilities.

Non-Contractual Liabilities

Look beyond obvious risks to identify what you could call "dormant obligations."

The technology sector can serve as an example. Companies with large software codebases often carry what is called "technical debt" – the cost of updating legacy systems. While this doesn't appear on any balance sheet, it can require massive future investments that the company will not only have to make to continue using those systems but also to keep up with competitors.

Technical debt is non-contractual but is a cost the company will have to incur in the future. Better be prepared by understanding the size of these future expenditures.

We can go a step further and map some of these potential liabilities. At this point, I'm thinking about future expenditures that the company will have to make but that are not currently under contractual obligations.

These liabilities generally arise from internal decisions, strategic initiatives, or regulatory requirements rather than formal agreements with external parties.

A good approach to think about this is to develop what I call "temporal vision" – the ability to see how current “gaps” might evolve into future. What technology the company is going to need? What skills are the employees going to need? Which community development programs the company will have to create? You get the idea.

Let’s see now the case for contractual liabilities that could be not fully represented in the financial statements.

Contractual Liabilities

Well, the typical example here was operating leases. Despite recent accounting changes under ASC 842 and IFRS 16, while most operating leases now appear on the balance sheet, the way they're calculated and presented can still be a little bit different than their true economic impact.

Look at the lease renewal assumptions built into the calculations. A company might report a lease liability based on a 5-year term, but their business model might depend on occupying those locations for 20+ years. So whats the real liability here? Ok, I won’t go into specific cases, but I thought I just mentioned it.

The most nebulous category - contingent liabilities - requires especially analysis. These depend on future events that may or may not occur. Accounting standards typically require recognition of liabilities on the balance sheet only if the obligation is probable and the amount can be reasonably estimated.

Let’s take a look at them in a table:

Ok, enough accounting. Let’s take a look at what we can learn applying the negative space approach to management earning calls.

Spotting Hidden Signals During Earnings Calls

Rather than listening to earnings calls, I find reading their transcripts far more effective for information processing and retention. The written format allows for deeper analysis, making it easier to identify subtle patterns that can reveal both emerging risks and opportunities.

Through reading these transcripts again and again, you start detecting some recurring patterns that often provide early signals of significant business developments. Let’s see some of them.

Discussing Key Metrics Patterns

When management stops discussing previously emphasized metrics, something could be happening.

A quick way to analyze this is through Koyfin's transcript keyword search capability. Take Netflix as an example: I can search for specific terms across all transcripts dating back to 2006. While there are natural ebbs and flows in the frequency of certain terms, this analysis can reveal how management's tone evolved around key topics.

Look at how they talk about “church” over the quarters. Particularly approaching the subscriber churn spikes that occurred during 2022. Reading these discussing one after the other would give you a better perspective compared just to listen to the call once every three months.

Question Deflection Patterns

This pattern emerges when executives begin behaving more like politicians than business leaders, shifting away from candid communication with shareholders and analysts toward more evasive or carefully crafted responses.

When executives redirect a specific question several times across different earnings calls, it often signals underlying issues. Here are the patterns to watch for:

Generic-to-Specific Ratio: When management responds to specific questions with general answers.

Historical Reference Shifts: When management suddenly stops comparing current performance to historical periods.

Segment Detail Reduction: When management reduces segment-specific commentary, could be masking underperformance in key divisions.

Strategic Context Shifts

Pay particular attention to changes in how management frames strategic initiatives. Some of the patterns to look for:

Track the "strategic initiative vocabulary" - the specific terms management uses to describe their key programs

Monitor the frequency and context of these terms across quarters

Note when previously emphasized initiatives receive reduced airtime

Earnings Call Tracker: A Practical Approach

A Google Sheet is all you need. I call this a "narrative consistency tracker." With a simple table you can track:

Key metrics mentioned in previous calls

Frequency of specific product or segment discussions

Competitive positioning commentary

Forward-looking statement specificity (other than guidance)

It easier when you showcase the information this way. It allows you to compare these elements across at least a few quarters to establish patterns. Pay particular attention to subtle shifts in emphasis rather than just obvious omissions.

The most valuable insights often come from combining these patterns. For example, when you see reduced forward-looking commentary coinciding with decreased segment detail and increased question deflection, could be an indicator of upcoming challenges.

A Call-to-Action For an Active Approach

Healthy skepticism in financial analysis isn't about being negative - it's about being thorough. To truly understand and measure the negative space surrounding a company, you must maintain active skepticism.

Take the case of Under Armour that we discussed before. Companies that consistently meet earnings estimates like clock work for several consecutive quarters are rare. Does this perfect consistency in financial reporting mask underlying volatility through manipulation? When everything looks too perfect, it often isn't.

You have to ask all the time:

What related information isn't being shared?

Why might this information be missing?

How can we verify this through alternative means?

For this, you can use a systematic framework that looks for three key types of anomalies:

First, compare disclosure levels across peer groups. When one company provides significantly less detail than its competitors about a particular metric, it could signal underlying issues.

Second, track changes in reporting granularity over time. Companies reducing disclosure deserve an in-depth look. Is management attempting to obscure deteriorating business conditions?

Third, monitor the relationship between primary and secondary disclosures. For instance, if a company's footnotes about inventory valuation become less detailed while inventory levels rise, it might signal upcoming write-downs. We discussed many examples above.

Remember, the goal isn't to actively seek problems but to develop a complete understanding. Sometimes, what appears to be missing information has a perfectly reasonable explanation. The key is distinguishing between intentional omissions and legitimate business practices.

Conclusion

Instead of focusing solely on what companies report, instead of blindly believing management story, we must develop systematic methods for identifying and analyzing the information that is not readily obvious.

You could expand this type of analysis to examine other dimensions surrounding a company, such as customers, competitors, and regulators. Maybe that could be the topic for a future article.

Remember, just as Escher's birds dissolve into water and fish fade into sky, a company's true nature is most revealed in the unspoken, the unseen, and the overlooked.

Companies must adhere to specific regulations when reporting segments. According to SEC Regulation S-K, segments representing 10% or more of total consolidated revenue, combined profit or loss, or combined assets must be disclosed. Any changes in segments must be reported on Form 8-K within four business days, along with explanations and restated prior period information. Additionally, FASB ASC 280 outlines criteria for operating segment reporting, including engagement in business activities, availability of discrete financial information, and regular review by the chief operating decision-maker.

https://www.edspira.com/did-under-armour-commit-fraud/

https://www.sec.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2021-78

“Further differences might exist in such areas as software development costs, where US GAAP provides specific detailed guidance depending on whether the software is for internal use or for sale. Other industries also have specialized capitalization guidance under US GAAP (e.g., film and television production). The principles surrounding capitalization under IFRS, by comparison, are the same, whether the internally generated intangible is being developed for internal use or for sale.”

https://viewpoint.pwc.com/dt/us/en/pwc/accounting_guides/ifrs_and_us_gaap_sim/ifrs_and_us_gaap_sim_US/chapter_6_assetsnonf_US/66_internally_develo_US.html

“Under IFRS, capitalization of intangible assets is permitted under specific conditions. The asset must be identifiable, controlled by the company, and expected to generate future economic benefits. Additionally, the cost of the asset must be reliably measurable, technically feasible, and backed by the intent and ability to complete the asset".”

https://viewpoint.pwc.com/dt/us/en/pwc/accounting_guides/ifrs_and_us_gaap_sim/ifrs_and_us_gaap_sim_US/chapter_6_assetsnonf_US/66_internally_develo_US.html