Unearthing Real Estate Gems: Four Recent Examples of Unlocking Hidden Value in Public Companies’ Balance Sheets

From locked assets to cash windfalls: how property plays boost financials and stock prices

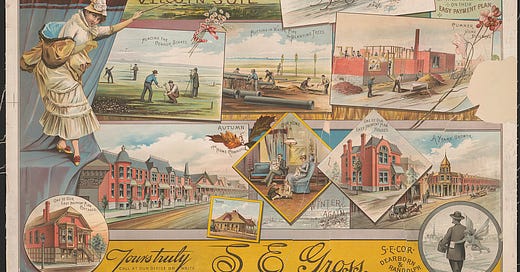

Dear Reader: In 1848, when S.E. Gross meticulously documented the real estate development process—from raw land to finished home—in colorful chromolithographs (image above), the fundamentals of property value were already being established. Almost two centuries later, these same principles continue to drive opportunity, though often hidden beneath balance sheets. Today’s experienced investors, like the land prospectors of America’s expanding 19th century, recognize that extraordinary value sometimes hides in plain sight. This modern treasure hunt is not for gold but for overlooked real estate assets tucked within underappreciated companies, where market inefficiencies and investors’ neglect create openings for exceptional returns that market participants have yet to discover. That’s why I’m dedicating today’s article to analyzing the process of uncovering such companies. Let’s dive in!

If you've just discovered my newsletter, subscribe to receive all new articles directly in your inbox.

You can also download a printable PDF and DOC version of the article using the following links:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1zBohZurtFzxfjLT8UvlxRZWVckmBwULcHktbzcEmSgs/edit?usp=sharing

The Untapped Value of Corporate Real Estate

As investors, we are always on the hunt for hidden value, and it’s not uncommon for a mid-cap or small-cap firm to sit on land and buildings bought decades ago, carried on the books at outdated prices, yet now worth a fortune. You may have seen many investment theses based solely on this premise.

Now, in some cases, a company’s property portfolio alone could be worth as much as (or more than) its entire market cap—yes, a potential goldmine the market has yet to fully price in.

Can it be that easy? Of course not—there are always nuances. In this in-depth report, I explore how to identify such opportunities and highlight case studies where hidden property assets have led, or could lead, to significant financial windfalls. But first, let’s explore why corporate real estate can be undervalued.

Landlocked Legacy: Why Corporate Real Estate Is Often Undervalued

Many companies – especially older mid- and small-cap firms – have accumulated real estate over time. Accounting rules require that property be recorded at historical cost (minus depreciation), not current market value. Over decades of inflation and urban development, the true market worth of these assets can far exceed their book value.

In other words, a building purchased for $1 million in 1970 might still sit on the balance sheet at $1 million (or even less after depreciation), even if it’s now on prime land worth $20 million. This gap between book value and market value creates hidden equity that financial statements don’t obviously reveal.

Moreover, the market often values companies based on earnings or cash flow, not on the breakup value of assets. So, if a firm's core business is struggling or just modestly profitable, the market might assign a low earnings multiple and overlook asset values.

Real estate can become “trapped” value – substantial, but not reflected in the stock price because it doesn’t contribute much to reported earnings (especially if the property is self-used, generating no rent).

We can find examples of this situations in all kind of companies, from retailers to industrial firms and we will see some of them below.

In short, corporate real estate tends to be undervalued due to conservative accounting, investor focus on income over assets, and sometimes management’s reluctance to monetize property. This sets the stage for opportunistic investors – especially in the mid- and small-cap arena – to capitalize on this valuation disconnect.

When the market finally recognizes these hidden assets (through asset sales, spin-offs, or activist pressure), the stock can re-rate sharply upward.

So, what are the key indicators we can use to identify this companies?

Key Indicators for Identifying Hidden Real Estate Value

Below there are a few quick and easy indicators and strategies for investors to find these hidden gems:

Significant Property Ownership – Look for companies that own a large portion of the facilities they operate in (stores, factories, land, etc.) rather than leasing. Annual reports and 10-K filings often list the number of owned vs. leased locations. A high ratio of owned properties may suggest substantial real estate assets that could be undervalued.

Low Book Value vs. Market Reality – Check the balance sheet line for Property, Plant & Equipment (PP&E), specifically the land and buildings. If a firm has owned properties for decades, the book value of land (which isn’t depreciated) might be far below current market, and buildings might be fully depreciated. Whenever we see large land holdings recorded at old values, there’s a good chance there’s hidden worth.

Sum-of-the-Parts Gap – Perform a sum-of-the-parts (SOTP) valuation. Estimate what the core operating business is worth (e.g. via P/E or EBITDA multiples assuming it paid market rent for its facilities), then separately estimate the real estate value (using market comps or rent capitalization). Adding those together can reveal a higher intrinsic value than the current market cap. If the stock trades well below this sum-of-parts, the real estate is likely not fully priced in.

Activist or Insider Activity – Activist hedge funds usually look for this hidden assets. If we see an activist investor taking a stake in a sleepy small-cap while talking about “unlocking value,” there’s a good chance real estate is involved. I will share some examples below. Insiders may also act – e.g., if management suddenly explores a REIT spinoff or sale-leaseback, it signals they see unrecognized value.

Recent Transactions or Comps – If similar companies have sold real estate or spun off property into a REIT, use those comps. For example, when Darden Restaurants (parent of Olive Garden, a larger company) spun off its restaurant properties into an REIT, it set a precedent for how the market values restaurant real estate. Likewise, sale prices of nearby land can guide us. By comparing such comps to what a target company holds, we can have an idea of the potential mismatch in valuation.

So, the general idea here is to treat the company's real estate as a separate business on paper. Evaluate it independently from the operating business. If that analysis reveals a sum-of-parts value much higher than the current stock price, we may have found a hidden real estate play.

Ok, now let’s see some case studies.

Case Studies: Companies with Undervalued Real Estate Assets

Let’s look at four historical examples where real estate holdings represented huge hidden value.

These case studies show how unlocking that value could result in significant upside for shareholders. Each of these companies was initially overlooked or undervalued by the market, until the real estate story became known.

Dillard’s – A Retailer Hiding a Real Estate Empire

Dillard’s (DDS) is a regional department store chain that for years was valued mainly on its retail performance. But Dillard’s also owns most of its store buildings and the land beneath them – about 44.1 million square feet of owned retail space out of ~50 million sq ft total. This makes it unusually asset-rich. By 2017, with brick-and-mortar retail in a slump, Dillard’s stock was languishing around the $50–$60 range (market cap roughly $2 billion). That’s when activist investors suspected an opportunity.

Snow Park Capital, a hedge fund, took a stake and argued that Dillard’s real estate was dramatically underappreciated. In fact, Snow Park’s managing partner Jeffrey Pierce famously remarked: “Dillard’s is essentially an underleveraged real estate company masquerading as a low productivity retailer.”1 His fund estimated the value of Dillard’s vast real estate holdings is well north of $200 per share.

To put that in perspective, if true, the real estate alone was worth 3–4 times the stock price at the time. Snow Park further noted that if Dillard’s rented out its locations to more productive retailers, the rental income might exceed Dillard’s entire operating earnings as a retailer – highlighting how the real estate was arguably the more valuable business within the company.

Now, why was this value hidden? Dillard’s properties were carried at old book values. The company had little debt (“underleveraged”), so it wasn’t forced to monetize assets. And management had been resistant to activists in the past. But the sheer scale of the property portfolio made it a good target.

What happened? Dillard’s resisted pursuing a major real estate spinoff. However, the market eventually caught on. As retail conditions improved post-2020 and some investors bought into the 'real estate thesis,' Dillard’s stock increased significantly. By 2021, DDS shares were trading in the mid-$200s, and in 2022, they reached over $300. Of course, the post-pandemic retail recovery and improved margins contributed significantly to the stock price movement, but having the real estate cushion may have helped as well.

Bob Evans – Unlocking Value via Sale-Leaseback and Spinoff

This is another old example I found and one that I find extremely interesting.

Bob Evans Farms (BOBE) was a small-cap company that ran a chain of family-dining restaurants and sold packaged food products (sausage, side dishes, etc.). By 2013, its stock was around $55–$60 per share (market cap ~$1.1B), and some believed it was undervalued. The main reason? Bob Evans owned the land and buildings for nearly all its 500+ restaurants – a relatively rare asset-heavy model in the restaurant industry. Those properties were on the books at low cost, while the restaurant operations themselves were experiencing sluggish growth.

Activist investor Sandell Asset Management took a ~5% stake and pushed a bold plan: split the food business and restaurant business, and execute a massive sale-leaseback2 of the restaurant properties to unlock cash. Sandell argued that Bob Evans was suffering a “conglomerate discount” by keeping two unrelated businesses together and not monetizing its real estate.

In a letter to the board, Sandell outlined how a sale-leaseback of the company’s 482 owned restaurants could generate over $1 billion in proceeds. In their analysis, Bob Evans could use part of that cash to pay down debt and repurchase shares at $58 each, driving the stock price up.

They estimated the post-deal intrinsic value of Bob Evans at $73 to $84 per share (roughly 40% higher than the pre-transaction price).

What happened? Bob Evans management initially resisted, but pressure mounted. In 2016, the company completed a smaller sale-leaseback of 143 properties for ~$200 million, indicating that the real estate valuations were real.

Ultimately, in 2017, Bob Evans decided to sell its entire restaurant division to a private equity firm for $565 million. That sale effectively realized the value of the restaurant real estate (the buyer assumed the properties, and presumably valued them in the deal).

After selling the restaurants, Bob Evans was left as a pure packaged-food company, which shortly thereafter was acquired by Post Holdings for a good premium.

In the end, an investor who bought in around 2013 (when Sandell began the activist process) saw a substantial gain as the pieces of Bob Evans were sold off at higher valuations than the market originally implied.

Bob Evans’ case study is a clear example of hidden real estate value being unlocked through strategic actions.

The key metrics: hundreds of owned locations, which were more valuable than the market appreciated. When those were monetized (via sale-leaseback and then the outright sale of the division), the shareholders reaped the rewards. Sandell’s thesis proved correct – the sum of the parts (food business + real estate-heavy restaurant business) was far greater than the whole company’s initial valuation.

Aerojet Rocketdyne (Gencorp) – Defense Contractor with Vast Land Holdings

It’s not only retailers and restaurants that sit on under-the-radar real estate. Aerojet Rocketdyne3, known as Gencorp in the early 2010s, is a mid-cap aerospace and defense company that also had a real estate segment.

Now, how does a rocket engine manufacturer end up in real estate? History and legacy assets. Gencorp inherited 12,200 acres of land near Sacramento, CA – originally acquired in the 1950s for rocket testing and manufacturing. Over time, much of that land became excess to Aerojet’s needs and ripe for development (they even set up a subsidiary “Easton” to entitle ~6,000 acres for potential new housing and commercial projects).

Yet, in 2012, Gencorp’s balance sheet didn’t reflect much value for this land at all. The company’s net PP&E was recorded at only $144 million, with land at a mere $32.8 million on the books. In fact, due to past accounting write-downs and pension liabilities, Gencorp had a negative book equity at the time – hardly an obvious candidate for asset-based value. But investors who looked deeper saw the disconnect: thousands of acres in a growing metropolitan area (Sacramento) had significant market value that was essentially hidden in Gencorp’s financials.

At the time, Gencorp’s market cap was around $700 million. If the land could be sold or developed, it might bring in hundreds of millions (if not more), on top of the profitable rocket engine business. Essentially, investors were getting the real estate for pennies on the dollar. The company was already leasing some parcels (earning rental income) and working on entitlements, which indicated a path to monetization.

What happened? Aerojet Rocketdyne’s story took a few twists. The company made a major acquisition (Rocketdyne from United Technologies) to grow its core business, taking on debt in the process. This perhaps shifted focus away from immediate land sales. However, over the following years, Aerojet did slowly start to sell land and also benefited from the general rise in real estate values. By 2015, it had sold some acreage to developers, and by 2020, it was reporting progress on its Easton development (now known as Easton Park, etc.). The stock indeed rose significantly over the decade.

By 2022, Aerojet Rocketdyne’s market cap was in the $4–5 billion range, and it was acquired by L3Harris in 2023 for $4.7 billion – a multiple of the price back when the real estate thesis was identified. While that increase wasn’t solely due to land (the defense business grew too), investors who recognized the hidden land value had a margin of safety and an extra catalyst in the stock. This is something I always try to look for in companies I own: an extra margin of safety, whether in real estate, participation in other companies, or any other asset class.

The lesson from Aerojet/Gencorp is that even in companies where real estate isn’t the core business, legacy land holdings can be extremely valuable. When those assets are in attractive locations and held at low book values, there is a real chance for a payoff. It may require patience (as real estate development is slow) but can significantly boost shareholder value in the long run.

Limoneira – Farming Company with Fertile Land (and Balance Sheet)

Limoneira (LMNR) is a small-cap agribusiness that grows lemons, avocados, and other crops in California and Arizona. Founded over 100 years ago, it’s also essentially a land company – owning 10,500 acres of agricultural land, plus water rights and real estate development entitlements.

For years, Limoneira’s stock traded mainly on its farming earnings, which can be volatile (impacted by crop prices, yields, weather, etc.). However, some investors noted that the underlying value of Limoneira’s land greatly exceeded what the market was crediting.

A large portion of Limoneira’s acreage is in Ventura County, California – a region with increasing suburban development. The company had a venture to develop a master-planned community called Harvest at Limoneira on some of its property (a partnership to eventually build over 2,000 homes). In addition, Limoneira owned orchards and ranch land that had appreciated over decades. Yet, the stock (in the high teens per share, roughly $250–$300 million market cap in recent years) did not reflect the market value of these assets.

This became evident when Limoneira started selling pieces of its land as part of a strategic shift. In late 2022 and early 2023, the company sold non-core assets including a 17-acre parcel for $8 million and, more dramatically, 3,537 acres in Tulare County for $100 million.

In the span of a few months, Limoneira raised about $130 million from land sales – nearly half of its entire market cap at the time. These transactions validated that the land carried on its books could fetch significant sums in the open market.

Even after those sales, Limoneira still holds thousands of acres (including the joint-venture development land). The company signaled its intent to pursue more asset sales and even explore strategic alternatives (you know, code for possibly selling the whole company or other big moves). This suggests that the real estate value gap may still not be fully closed – management themselves recognize the stock is undervalued relative to the sum of its parts.

For investors, Limoneira has been a lesson in hidden NAV (Net Asset Value). Agricultural land and water rights don’t show up at fair value on financial statements, and farming profits alone don’t justify a high stock price. But when you start monetizing the land bank, the hidden value becomes crystal clear. Limoneira’s stock responded positively to these sales (up ~20% after the $100M sale announcement).

These examples showcase different industries – retail, restaurants, aerospace, agriculture – all sharing a common theme: significant real estate holdings that the market initially underpriced. By recognizing the signs and doing the homework on asset values, investors in these names positioned themselves for substantial gains when the properties’ true worth started to be realized.

Back to Cash: How Unlocking Real Estate Pays Off

Identifying a hidden real estate play is just the first step. The real magic happens when that value is unlocked. Let’s analyze how unlocking the value can impact a company’s financials and stock price, using the case studies above as a guide.

Typically, value is unlocked through one or more of these actions: asset sales (while correctly using the proceeds), sale-leaseback arrangements, spin-offs/REIT conversions, or outright liquidation of the company.

Immediate Cash Infusion and Debt Paydown: When a company sells a property or executes a sale-leaseback, it receives a lump sum of cash. This can improve the balance sheet. For instance, Bob Evans’ $200M+ in sale-leaseback proceeds allowed it to pay down debt and fund share buybacks. By reducing debt, we lower enterprise value and interest expense, which can boost equity value. In Bob Evans’ case, Sandell’s proposal was to use ~75% of the $1.08B projected real estate proceeds to repurchase stock. Buybacks at a depressed price increase each remaining shareholder’s stake. Essentially, monetizing the real estate translated into direct shareholder return via buybacks.

Improved Return on Assets and Earnings Quality: Oddly, owning too much low-yield real estate can depress a company’s return on assets (ROA) and even operating margins (due to property upkeep costs). Once assets are sold and capital is redeployed into the core business or returned, the company can show improved operating metrics. However, one must account for new lease expenses if it was a sale-leaseback. A smart analysis will recast the company’s income statement as if it’s renting those properties. If the core business can still earn strong profits after paying rent, then the sale-leaseback made sense. If not, that signals the business might struggle with the new cost structure. In practice, many undervalued-asset companies have underutilized real estate – meaning they can shed assets and not hurt operations much. Dillard’s, for example, could theoretically sell some stores and lease them back without cratering its profitability, because its stores were large and not fully productive per square foot. The rental expense would be covered by bringing in other tenants or just the improved efficiency of capital use.

Sum-of-Parts (SOTP) Value Realization: When a company spins off real estate into a separate entity (like a REIT) or sells a division with lots of property (as Bob Evans did), it effectively forces the market to value that part independently. Often, the parts are valued higher separately than together. For example, if Bob Evans had spun off an “Bob Evans REIT” owning all its restaurant buildings, that REIT might trade at, say, a 5-6% capitalization rate. If the restaurants paid $60M in total rent, the REIT could be worth $1 to $1.2 billion on its own (since $60M at a 5% cap rate = $1.2B). Meanwhile, the remaining food business could be valued at a typical food company multiple. Combined, that sum might beat the original integrated valuation.

Liquidation: Sometimes the ultimate way to unlock value is to sell everything and return the cash. To illustrate the extreme end of unlocking value, consider Luby’s, a Texas-based cafeteria chain. Luby’s decided in 2020 to liquidate itself – selling off all restaurants, properties, and assets – because its parts were worth more than the stock price. Over the next couple of years, Luby’s sold real estate, including dozens of restaurant properties for tens of millions of dollars. As the liquidation progressed, the company regularly updated its estimated liquidation value per share, and it kept rising. By mid-2021, Luby’s estimated about $4.13 per share in liquidating distributions4, up from initial estimates around $3.85 – and well above the sub-$2.50 share price before liquidation was announced. While liquidation is a last resort (and not the plan for most going concerns), it proves the point: real estate carries tangible value that will be realized eventually, one way or another.

To sum up, unlocking real estate value can materially strengthen a company’s financial position: reducing leverage, increasing cash, and often refocusing the business on its core competency. For shareholders, these moves tend to act as a catalyst – the stock price converges toward the higher intrinsic value once the market sees the cash or spun-off shares in hand.

Risks and Considerations: Not Every Hidden Asset Pays Off

Before one gets too excited about finding the next real estate treasure trove, it’s important to acknowledge the risks and complications involved in these situations. While the upside can be large, there are several factors that can interfere with the realization of that value:

Management Reluctance or Misalignment: A company’s leadership might simply refuse to sell or separate its real estate assets, no matter how compelling the logic. Often, managers like the control and stability that owning property provides. If management is entrenched or uninterested in shareholder value (sometimes preferring empire-building or fearing change), the hidden value can remain locked indefinitely. Activist investors may or may not succeed in changing their minds.

Operational Dependence and Emotional Attachment: Some assets are core to the company’s identity (think flagship stores or a campus built by a founder). There can be emotional or practical resistance to selling these. Additionally, sale-leasebacks increase fixed costs (rent), which could squeeze future earnings if the business isn’t robust. A sale-leaseback essentially swaps an asset for cash, but commits the firm to ongoing payments. If the underlying business is declining (say, a retailer facing e-commerce headwinds), taking on rent obligations could backfire.

Market Conditions and Timing: Real estate value can be cyclical. A parcel might be highly coveted in a boom, but if the market turns (recession, retail downturn, etc.), buyers disappear or values drop. We saw this with some mall properties: what looked extremely valuable in 2015 had fewer takers by 2018 as malls struggled. In short, “use it or lose it”: failing to unlock value in time can mean the value erodes.

Tax and Transaction Costs: Unlocking value isn’t free. There can be significant taxes on asset sales (capital gains taxes if the properties’ tax basis is low) unless structured cleverly (some deals use REIT spins or like-kind exchanges to defer taxes). Transaction costs like broker fees, appraisal, and legal expenses also eat into proceeds. Investors must consider the net value from a sale, not just gross. In a REIT spin-off, there’s complexity in setting up a new company and ensuring it has the right financial structure (and the parent company might owe taxes if not done carefully under IRS rules).

Value Trap Risk: A stock can stay undervalued for a long time. The “hidden real estate” thesis might not play out as expected. Perhaps the assets are harder to sell than assumed, or their value on paper doesn’t translate into an attractive sale in reality (due to zoning, environmental issues, etc.). Gencorp’s land, for example, required environmental cleanup from its rocket testing days – an added cost and hurdle for development. Such factors can make the timeline to monetize long and uncertain. Investors need to be willing to wait or potentially face opportunity cost while nothing happens.

Post-Unlock Business Risks: If a company does monetize real estate, we have to assess what’s left. Sometimes, after selling assets, the remaining business is smaller or less competitive. It might deserve a lower multiple, offsetting some of the gain. In the Bob Evans scenario, after selling restaurants, the remaining packaged food company had to prove it could grow (it eventually was acquired, which solved that). But not every case ends in a tidy sale of the remainder; some become slimmed-down companies that still need a strategy (imagine a retailer that sold its stores and now leases them – did that actually fix the business, or just provide a short-term cash fix?). Ideally, unlocking real estate is part of a broader value creation strategy, not a one-off stunt.

External Factors: Real estate, by nature, is an illiquid asset. During processes to sell or spin off properties, external factors like interest rates, credit markets (affecting buyers’ financing), or even political/regulatory issues (zoning changes, landmark status on buildings, etc.) can influence outcomes. These are often out of the company’s control.

Given these risks, we should approach hidden real estate plays with a combination of optimism and caution. The upside can be good, but one should have a thesis on how and when the value will be unlocked.

Is there an activist involved or likely? Has management shown openness to asset sales? Are market conditions favourable for a sale/REIT spin in the near term? Without a catalyst, a stock can remain a “value trap.” On the flip side, a clear catalyst (like a company publicly announcing a strategic review of its real estate, or an activist launching a campaign) can significantly de-risk the situation and accelerate value realization.

Conclusion

For investors willing to dig into the filings, property records, and perhaps do a bit of real estate math, the rewards can be substantial. We’ve seen how recognizing these hidden assets in companies like Dillard’s, Bob Evans, Aerojet Rocketdyne, and Limoneira led to thesis-changing insights.

The process always comes back to fundamentals: what is the business worth, what are the assets worth, and is the market pricing both correctly? When there’s a large disparity – such as land valued on the books at pennies on the dollar of its true worth – it creates a margin of safety and a pathway for gain. For me, this is the key, using real estate as an extra margin of safety to back up my initial thesis.

Whether through activist campaigns, strategic sales, or corporate restructuring, these hidden assets eventually find their way to proper valuation. The journey may require patience, but the rewards can be exceptional—sometimes doubling or tripling shareholder value when the market finally acknowledges what was there all along.

When done right, investing in companies with undervalued real estate, it’s value investing at its finest – unearthing the dollars that everyone else left on the table. For those with a good eye, the next small-cap with hidden real estate might just be the next big winner in your portfolio.

If you read all the way here, I hope you found this post valuable. If you haven't subscribed yet, I encourage you to do so to keep receiving insights like this. If you're already subscribed, please consider sharing this post with someone who might benefit. In any case, hitting 'like' is greatly appreciated—it helps Substack recognize and distribute quality content.

Retail Dive. (2017, August 1). Activist investor urges Dillard's to sell off its real estate. Retrieved from https://www.retaildive.com/news/activist-investor-urges-dillards-to-sell-off-its-real-estate/448339/

For context, a sale-leaseback means Bob Evans would sell its restaurant real estate to a buyer (e.g., a REIT or private equity), then lease back the locations to continue operating. This unlocks immediate cash, but the trade-off is paying rent going forward. The activist felt this was worthwhile since the unlocked cash could be returned to shareholders or reinvested.

Aerojet Rocketdyne originated from GenCorp (formerly General Tire), which acquired Pratt & Whitney Rocketdyne in 2013 for $550 million, merging it with subsidiary Aerojet to form Aerojet Rocketdyne—combining solid-fuel and liquid-fuel propulsion expertise (e.g., RS-25 engines for NASA). GenCorp rebranded as Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings, Inc. in 2015, shifting focus to aerospace/defense. In 2023, L3Harris Technologies acquired the company for $4.7 billion, maintaining it as a subsidiary specializing in advanced propulsion and hypersonic systems.

Actual distributions ultimately exceeded initial estimates, reaching $4.24 per share by 2025.

Great write up.

Ingles Markets is another one.

"The fair value of the land has been estimated to be ~$2.75bn and growing, well in excess of Ingles’ current market capitalization, currently around $1.15 billion. The implication being that once the assets are stripped out of the market cap, the business, as a going concern, is being valued at less than zero. An alternative interpretation is that you could buy the business and inherit a very valuable land portfolio for free."

Full analysis here: https://rockandturner.substack.com/p/ingles-or-ingles-who-cares-its-cheap

For people into this kind of stuff there is some fun information on pages 16 and 17 of this supplement.

https://ir.kennedywilson.com/~/media/Files/K/Kennedy-Wilson-IR-V2/documents/4q-24-supplemental-and-release.pdf