Why Failed Companies’ Hidden Tax Assets Might Be Your Most Profitable Investment Yet in 2025

Turning tax losses into attractive investment setups: a guide to understanding and profiting from NOL-rich companies

Ok, I knew that 2025 wasn’t going to be a walk in the park, but I definitely didn't have this level of...eventfulness on my bingo card. So, what do we do? Well, there are a lot of interesting things to look at. Today, I’ll discuss investing in NOL vehicles.

With the recent economic turbulence, many companies are facing or will face significant loss carryforwards, so I guess interest is rising in how these 'tax-advantaged' shells might be leveraged.

I'm analyzing an NOL vehicle opportunity right now, so I've decided to do a bit of a deep dive into the topic in general.

In this post, I’ll break down what NOLs are, explain why NOL-rich stocks can be great opportunities, highlight the risks and pitfalls to watch out for, and outline strategies to capitalize on them. I’ll even highlight a few real-world NOL plays that are unfolding right now in future posts.

So, What On Earth Is an NOL Vehicle?

Let’s start with the basics.

Net Operating Losses (NOLs) happen when a company’s tax-deductible expenses exceed its taxable revenues in a given year – in plain English, the company lost money and can’t use all its deductions.

Rather than let those extra deductions go to waste, the tax code lets businesses carry those losses to other years. They can sometimes be applied to past years to get a refund (carryback), or more commonly carried forward to offset profits in the future.

In other words, a big loss today can be used to cancel out taxable income tomorrow. If a startup blows a bunch of cash on R&D and runs at a loss, those losses become tax credits for when it finally makes money.

Accountants record NOLs as deferred tax assets on the balance sheet – essentially saying “when you make money again, you won’t owe taxes on the first chunk of income.”

So far, nothing out of the ordinary, pretty simple.

Now, companies accumulate NOLs for all kinds of reasons: recessions, aggressive expansion, industry downturns, you name it. Over time, these losses can grow into massive NOL carryforwards.

A company with a huge accumulated loss and not much actual business left is called an “NOL vehicle” or “NOL shell.”

Think of it as once-struggling company that sold off its operations or went through bankruptcy, but kept the corporate entity alive because those tax losses have value. It’s basically a shell company whose biggest asset is a tax shield waiting to be used.

And what’s the ideal setup in these “NOL vehicles”? Well, I found 2 situations with exactly the kind of setup NOL investors would look for: huge NOL, tiny stock price and clear intention to do something about it.

As always, there’s nuance with this and tax rules matter here. I understand that, historically, U.S. companies could carry losses back 2 years and forward 20 years to offset profits. Recent tax law changes (like the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act) tweaked that: now you generally can’t carry back losses, but you can carry them forward indefinitely – with a catch.

You can only use NOLs to shelter up to 80% of taxable income each year. So even a company with a gigantic NOL still has to pay tax on 20% of its profits annually under current law. (Older NOLs from before 2018 are grandfathered under the old 20-year limit but without the 80% cap.)

The key thing: NOLs are valuable, but you can’t instantly zero out your taxes if you’re super profitable – you can shield a lot, but not necessarily all of the income at once.

Beware Of Section 382

There’s another big rule investors must know about.

The IRS doesn’t want companies trading NOLs like there’s no tomorrow (?), so Internal Revenue Code Section 382 is a set of rules to prevent “trafficking” in tax losses.

In simple terms, if a company with NOLs has a major ownership change (typically >50% change in ownership among 5%+ shareholders within 3 years), the use of those NOLs gets severely limited.

After such a change, the amount of NOL you can use per year is capped by a formula (basically the company’s market value at the time of change * a federal interest rate).

In practice, this can drastically slow down how fast the NOL can be used, stretching it over many years or even making much of it effectively unusable.

You can already guess that the rule is meant to stop profitable firms from simply buying loss-making companies just to use their NOLs.

So get someone take too large a stake or engineer a buyout without care, and you could trigger an ownership change that destroys most of the NOL’s value.

Companies with big NOLs know this, which is why many adopt NOL “poison pills” – special rights plans that prevent any outsider from accumulating 5% or more of the stock (VERY IMPORTANT in one of the special situations I’m looking at and where they’ve already done this).

Why I Like NOL Setups

As I mentioned above, this are special situations and can have unique upsides that the market usually is not aware off in general.

When you are looking at a company that is NOL-heavy there are 3 reasons that make them more appealing:

Tax-Free Profits (The NOL Tax Shield): A NOL carryforward is basically a tax credit in your pocket. More of the profit falls straight to the bottom line. All else equal, a business with a big NOL can earn the same pretax profit as a competitor but deliver higher after-tax earnings because Uncle Sam is taking a smaller cut. This tax shield can make a huge difference. The bottom line: when a struggling company finally rights the ship, its NOLs can supercharge the comeback by letting new profits come in tax-free.

Takeover Bait (M&A Opportunities): I think this one is the most attractive characteristic from an investor point of view. Companies with large NOLs can become attractive takeover targets or merger partners. A profitable acquirer might look at an NOL-rich company and see a chance to buy it and use its NOL to shield the combined entity’s future income from taxes (within the limits of Section 382, of course). A classic play is to merge a healthy, profit-generating business into an NOL “shell” company – effectively injecting profitable operations into the NOL vehicle so those profits get absorbed by the existing NOL, resulting in little to no taxes for a while. This can sharply increase the post-merger cash flows of the combined business and boost the deal’s overall value.

Turnaround Boosters: Some NOL vehicles are companies that fell on hard times but still have a pulse – a viable core business or valuable assets – making them potential turnaround stories. They accumulated big NOLs during the rough years, but with the right changes (new management, restructuring, or simply an industry upcycle) they could swing back to profitability. If that happens, investors reap a double reward: first from the business recovery itself (shares go up because the company is healthy again), and second from the NOL tax shield that lets those newfound profits flow in largely tax-free. This one-two punch can dramatically accelerate the impact of a turnaround on equity value.

The Catch: Yes, There Are Always Risks

Ok, I don’t know how excited you are so far but, let’s be clear: these opportunities come with plenty of hair and complexity. The same features that make NOL vehicles interesting also generate unique risks. Here are the major ones you need to keep in mind:

Tax Code Risks (Section 382): I touched on this earlier, but it bears repeating – Section 382 is the ultimate danger for NOL investors. If there’s a significant ownership change, the NOL’s usability can be slashed to a trickle (or completely lost). Always check if the company has a poison pill or other safeguards in place – they’re annoying if you wanted to accumulate a big position, but they ultimately protect the NOL (and by extension, your investment thesis).

No Profits, No Prize: An NOL, by itself, does not make a business valuable. It’s only useful if the company eventually generates taxable profits for it to offset. If the underlying firm remains unprofitable or stagnant indefinitely, the NOL is just a dormant asset gathering dust. In the worst case, if the company never returns to profitability (or for older NOLs, doesn’t do so before they eventually expire), those tax losses expire unused – worthless to shareholders. So as an investor, you can’t just buy a stock for the NOL and call it a day; you have to honestly assess the company’s ability to make money down the line. An NOL-laden shell with no real plan or prospects to turn a profit is just a shell. Remember: NOLs don’t guarantee future earnings – they simply enhance earnings if and when those earnings materialize. No profits, no tax savings, no payoff.

“Damaged Goods” Stigma: Companies carrying large NOLs usually have a history of losses, maybe even bankruptcy. That kind of track record can leave a bad stigma in the market. Other investors might be skeptical (with good reason) about the company’s prospects, which can keep the stock price depressed for a long time. There may also be messy capital structures – leftover debt, warrants, or dilution from past restructurings – that make the equity less attractive. As a result, the stock might not fully reflect the value of the NOL asset for a while (if ever) because people simply don’t believe the company will use it. If you’re going to invest, you need the conviction to look past the surface grime.

Valuing NOLs is…Complicated: You might be tempted to take the NOL amount, multiply by the corporate tax rate (~21%), and say “hey, this NOL is worth that much in saved taxes.” In reality, the true value is usually a lot less, once you account for the time and uncertainty involved. Thanks to that 80% annual limitation, a company might need many years to fully use a huge NOL, which cuts down the present value of those tax savings. Future tax rates could change, which would also change the NOL’s value. And there’s always a chance the company won’t earn enough profits to ever use the full NOL. All these factors mean you typically have to heavily discount the face value of an NOL when assessing a company. Mispricing is common.

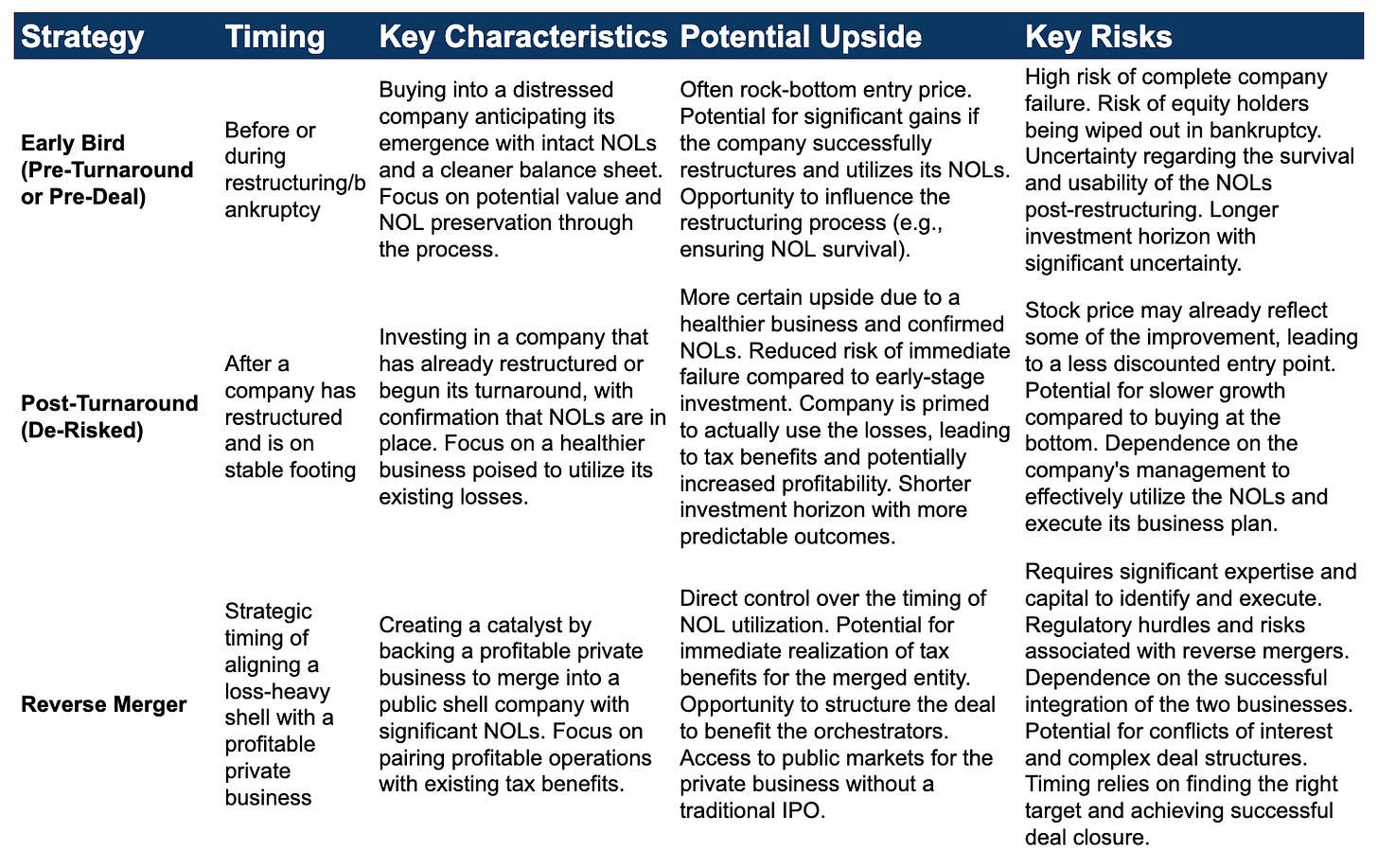

Time Your Entry (Catalysts Matter)

Now, timing can be everything in these plays. There are generally a few simple approaches. I summarized them in the table below:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1HijdxqUIcrESxKpKrYdZAl4huPj8qHu_Nn3lKJG-Smc/edit?usp=sharing

So, What’s Next?

Looking ahead, several factors could influence the landscape of NOL opportunities. NOL investing may be niche, but it changes a lot – it ebbs and flows with economic cycles and tax laws. Here are a few things to keep on your radar

Economic Cycles

Recessions and industry shake-outs tend to generate new NOL-rich companies.

Think about it: downturns cause lots of companies to rack up losses. When the economy or that industry recovers, some of those companies will still be around with big NOL carryforwards and improving businesses – a good combo.

I read somewhere that “downturns sow the seeds for the next wave of NOL opportunities.” Conversely, in extended boom times, fewer companies accumulate big NOLs (because everyone’s making money), so this strategy might be more scarce until the next recession hits.

Tax Law Changes

Tax policy isn’t fixed. Future changes in tax laws could either enhance or erode the value of NOLs. One obvious variable is the corporate tax rate: if it goes up, NOLs become more valuable (each dollar of NOL saves more tax); if tax rates go down, NOLs are a bit less valuable.

Going back to my point on how difficult is to value these things. If there’s a tax cut in the U.S. during the second half of the year, that could significantly affect the value of NOLs.

Lawmakers could also change the NOL rules themselves – for instance, they could loosen the 80% limitation or allow special carrybacks in certain cases (making NOLs more useful), or they could tighten things if they think companies are gaming the system (making NOLs less attractive).

While you can’t predict politics perfectly, it’s wise to factor in a margin of safety in your NOL valuations in case rules change. Favor situations that have a clear path to use NOLs under current law, and be a bit cautious about betting everything on an NOL that requires a decade to monetize (lots can change in that time).

The (NOL) Security I Like Best

As I mentioned at the beginning I’m doing some research on a NOL vehicle (may be even 2?) that I believe presents a really compelling setup.

In 2023, this company sold off its core business for cash, leaving the publicly traded entity as a cash-rich shell with minimal operations. What it does have is more than $2 billion in U.S. NOL carryforwards and around $150 million in cash (and no debt).

In effect, this firm is now a blank-check company with a huge tax asset – in some research I read they are calling it a SPAC that happened by accident.

A new CEO and board are actively hunting for an acquisition to deploy that cash and, importantly, utilize those NOLs.

The idea is to buy or merge with a profitable business, and the massive NOL would shield the profits of the combined company for years to come.

Shareholders are essentially holding a “call option” on a future merger, that will have almost tax free profits : if management lands a credible deal to inject a real business into this shell, well… the stock price could increase significantly.

Why?

Because right now the market cap is tiny relative to the cash and NOL value; any hint of a tax-driven deal could make the market suddenly price in those assets.

We’ll see what happens but, all told, this one is a timely NOL play: a once-fallen company that has reinvented itself as a potential merger vehicle with a giant tax shelter attached. Now it just needs the right target to make use of it.

I’ll share more details on this setup in the following days.

Happy (tax-efficient) investing ;)

Disclaimer

This newsletter (the “Publication”) is provided solely for informational and educational purposes and does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any security or other financial instrument, nor should it be interpreted as legal, tax, accounting, or investment advice. Readers should perform their own independent research and consult with qualified professionals before making any financial decisions. The information herein is derived from sources believed to be reliable but is not guaranteed to be accurate, complete, or current, and it may be subject to change without notice. Any forward-looking statements or projections are inherently uncertain and may differ materially from actual results due to various risks and uncertainties. Investing involves significant risk, including the potential loss of principal, and past performance is not indicative of future results. Neither the author(s) nor the publisher, affiliates, directors, officers, employees, or agents shall be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, consequential, or punitive damages arising from the use of, or reliance on, this Publication.